THE REVEALING PATTERN

By Alvin Heiner

The Reamer mansion was on trial.

It announced its own verdict—guilty!

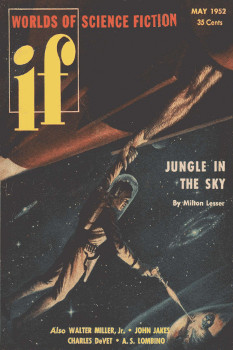

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

He was a man easily smiled at; a little birdlike individual carryingan umbrella and wearing upon his pink face a look remindful ofhappy secrets about to be revealed. He came to my desk during themidafternoon lull and said, "I am Professor Jonathan Waits. I have cometo avail myself of your facilities."

I had never heard it put quite that way before, but from ProfessorWaits, it did not sound stilted. It was the way you would expect him toput it. He beamed at the ceiling and said, "What a fine old library, mydear. I must bring Nicholas some time."

I gave him the smile reserved financial supporters and unknownquantatives and asked, "Could I be of service?"

He didn't get to it immediately. "I understand this library is fairlycrammed with old records—data on the historical aspects of this area.Personal histories and such."

He had a way of radiating his own cheerful mood. "Oh yes," I assuredhim. "It's an exceptional day when we don't sweep a D.A.R. or two outof the aisles come closing time."

This, according to his laugh, was quite good. He said, "I'm sure we'llget on splendidly, Miss—?"

"—Hopstead."

"Are you a native?"

"A New Englander from way back," I assured him. "Some of my ancestorsused to drink buttered rum with Captain Rogers."

"Then possibly you'd like to know about my work."

"I certainly would." And, strangely enough, I did.

"I am a researcher into the—well, the unusual."

"Psychic research?" I inquired, wanting him to know we New Englanderswere not dullards.

"No. Nothing to do with the supernatural at all. My work is to provethat all occurrences, however mysterious, are the logical result ofprevious actions of individuals; that superstitions are the result, notso much of ignorance, but lack of knowledge."

While I wrestled with that one, he said, "Maybe I could be a triflemore explicit."

"That would help."

His bright little eyes got even brighter. "Do you know, by chance, ofthe Reamer mansion over in Carleton?"

I certainly did. It was some thirty miles from Patterson, but as achild, I'd visited the place. All children within the radius hadvisited the Reamer mansion at least once. It was an ancient fifteenroom cockroach trap with such a history of death and violence behind itas to cause the kids to walk on tiptoe through its silent rooms. I toldthe professor I knew about it.

"It has been vacant for fifteen years," he observed.

"And will be vacant for twice fifteen more, I imagine."

"That's just the point. Superstition. Otherwise solid and sane peoplewouldn't dream of moving into the Reamer mansion. And it's so silly."

"It is?"

"Of course. And that's why I'm here. I intend to prove, so the moststubborn will understand, that the house itself has nothing whatsoeverto do with its own grim past; that the people who lived in it are toblame."

It was a dull day and he was such an apparently sincere little man thatI decided to keep the conversation alive. "I'm afraid you'll have ahard time proving it. Let's see—the first one was old Silas Reamer. Hecommitted suicide there. That was sometime around 1925. Then—"

"—His son, Henry Reamer, was found dead under