THE SPICY SOUND OF SUCCESS

By JIM HARMON

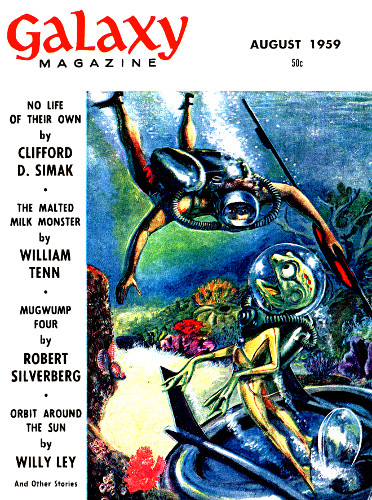

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine August 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Now was the captain's chance to prove he knew

less than the crew—all their lives hung upon it!

There was nothing showing on the video screen. That was why we werelooking at it so analytically.

"Transphasia, that's what it is," Ordinary Spaceman Quade stated witha definite thrust of his angular jaw in my direction. "You can take myword on that, Captain Gavin."

"Can't," I told him. "I can't trust your opinion. I can't trustanything. That's why I'm Captain."

"You'll get over feeling like that."

"I know. Then I'll become First Officer."

"But look at that screen, sir," Quade said with an emphatic swing ofhis scarred arm. "I've seen blank scanning like that before and youhaven't—it's your first trip. This always means transphasia—cortexdissolution, motor area feedback, the Aitchell Effect—call it anythingyou like, it's still transphasia."

"I know what transphasia is," I said moderately. "It means anelectrogravitational disturbance of incoming sense data, rechannelingit to the wrong receptive areas. Besides the human brain, it alsoeffects electronic equipment, like radar and television."

"Obviously." Quade glanced disgustedly at the screen.

"Too obvious. This time it might not be a familiar condition of manyplanetary gravitational fields. On this planet, that blank kinescopemay mean our Big Brother kites were knocked down by hostile natives."

"You are plain wrong, Captain. Traditionally, alien races neverinterfere with our explorations. Generally, they are so alien to usthey can't even recognize our existence."

I drew myself up to my full height—and noticed in irritation it wasstill an inch less than Quade's. "I don't understand you men. Look atyourself, Quade. You've been busted to Ordinary Spaceman for just thatkind of thinking, for relying on tradition, on things that have workedbefore. Not only your thinking is slipshod, you've grown careless abouteverything else, even your own life."

"Just a minute, Captain. I've never been 'busted.' In the ExplorationService, we regard Ordinary Spaceman as our highest rank. With myhazard pay, I get more hard cash than you do, and I'm closer toretirement."

"That's a shallow excuse for complacency."

"Complacency! I've seen ten thousand wonders in twenty years of space,with a million variations. But the patterns repeat themselves. We learnto know what to expect, so maybe we can't maintain the reactionarycaution the service likes in officers."

"I resent the word 'reactionary,' Spaceman! In civilian life, I wasa lapidary and I learned the value of deliberation. But I never gottoo cataleptic to tap a million-dollar gem, which is more than mycontemporaries can say, many of 'em."

"Captain Gavin," Quade said patiently, "you must realize that anoutsider like you, among a crew of skilled spacemen, can never be morethan a figurehead."

Was this the way I was to be treated? Why, this man had deliberatelyinsulted me, his captain. I controlled myself, remembering thefamiliarity that had always existed between members of a crew workingunder close conditions, from the time of the ancient submarines and thefirst orbital ships.

"Quade," I said, "there's only one way f