ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS

FRANKLIN'S

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

EDITED BY

O. LEON REID

HEAD OF ENGLISH DEPARTMENT, LOUISVILLE MALE

HIGH SCHOOL, LOUISVILLE, KY.

NEW YORK · CINCINNATI · CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1896 and 1910, by

American Book Company

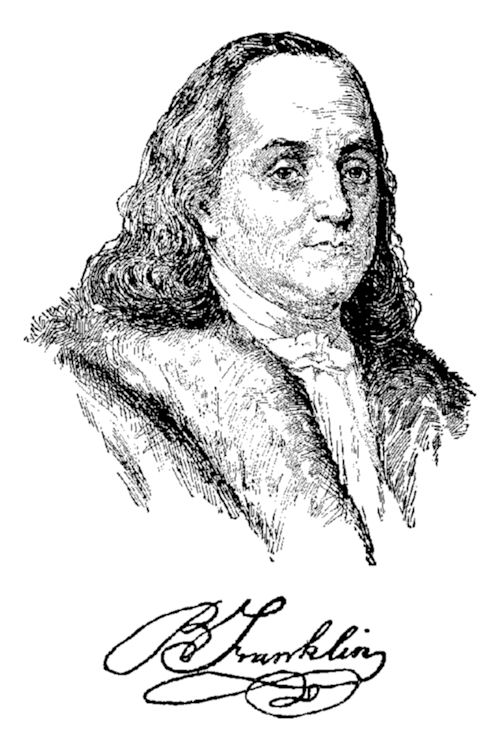

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

W. P. 12

INTRODUCTION.

When Franklin was born, in 1706, Queen Anne was on theEnglish throne, and Swift and Defoe were pamphleteering. Theone had not yet written "Gulliver's Travels," nor the other "RobinsonCrusoe;" neither had Addison and Steele and other wits ofAnne's reign begun the "Spectator." Pope was eighteen yearsold.

At that time ships bringing news, food and raiment, and lawsand governors to the ten colonies of America, ran grave chancesof falling into the hands of the pirates who infested the waters ofthe shores. In Boston Cotton Mather was persecuting witches.There were no stage coaches in the land,—merely a bridle path ledfrom New York to Philadelphia,—and a printing press throughoutthe colonies was a raree-show.

Only six years before Franklin's birth, the first newspaper reportfor the first newspaper in the country was written on the deathof Captain Kidd and six of his companions near Boston, whenthe editor of the "News-Letter" told the story of the hanging ofthe pirates, detailing the exhortations and prayers and their taking-off.Franklin links us to another world of action.

His boyhood in Boston was a stern beginning of the habit ofhard work and rigid economy which marked the man. For ayear he went to the Latin Grammar School on School Street, but [Pg 6]left off at the age of ten to help his father in making soap andcandles. He persisted in showing such "bookish inclination,"however, that at twelve his father apprenticed him to learn theprinter's trade. At seventeen he ran off to Philadelphia and therebegan his independent career.

In the main he led such a life as the maxims of "Poor Richard" [1]enjoin. The pages of the Autobiography show few deviationsfrom such a course. He felt the need of school training andset to work to educate himself. He had an untiring industry,and love of the approval of his neighbor; and he knew that morethings fail through want of care than want of knowledge. Hispractical imagination was continually forming projects; and, fortunatelyfor the world, his great physical strength and activity werealways setting his ideas in motion. He was human-hearted, andthis strong sympathy of his, along with his strength and zeal and"projecting head" (as Defoe calls such a spirit), devised muchthat helped life to amenity and comfort. In politics he hadthe outlook of the self-reliant colonist whose devotion to themother institutions of England was finally alienated by the excessesof a power which thought itself all-powerful.

In this Autobiography Franklin tells of his own life to theyear 1757, when he went to England to support the petition ofthe legislature against Penn's sons. The grievance of the colonistswas a very considerable one, for the proprietaries claimedthat taxes should not be levied upon a tract greater than thewhole State of Pennsylvania.

Franklin was received in England with applause. His experi