AUGUSTE RODIN

By

RAINER MARIA RILKE

Translated by Jessie Lemont and Hans Trausil.

New York

Sunwise Turn Inc.

1919

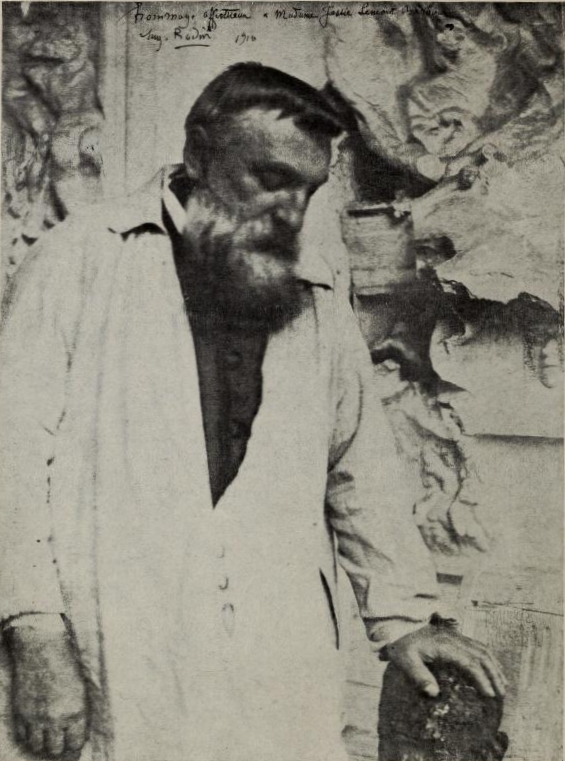

Rodin — photographed by Gertrude Kasebier

ARCHAIC TORSO OF APOLLO

We cannot fathom his mysterious head,

Through the veiled eyes no flickering ray is sent;

But from his torso gleaming light is shed

As from a candelabrum; inward bent

His glance there glows and lingers. Otherwise

The round breast would not blind you with its grace,

Nor could the soft-curved circle of the thighs

Steal to the arc whence issues a new race.

Nor could this stark and stunted stone display

Vibrance beneath the shoulders' heavy bar,

Nor shine like fur upon a beast of prey,

Nor break forth from its lines like a great star—

Each spot is like an eye that fixed on you

With kindling magic makes you live anew.

Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rendered into English by Jessie Lemont.

PREFACE

Rodin has pronounced Rilke's essay the supreme interpretation of hiswork. A few years ago the sculptor expressed to the translators thewish that some day the book might be placed before the English-speakingpublic. The appreciation was published originally as one of a series ofArt Monographs under the editorship of the late Richard Muther.

To estimate and interpret the work of an artist is to be creativelyjust to him. For this reason there are fewer critics than there areartists, and criticism with but few exceptions is almost invariablynegligible and futile.

The strongest and most procreant contact is that which takes placebetween two creative minds. This book of Rilke on Rodin is the fruit ofsuch a contact. It ripened on the tree of a great friendship for themaster. For a number of years Rilke lived close to Rodin at 77 rue deVarenne, in the old mansion surrounded by a beautiful park which wassubsequently dedicated to France by the artist and is now the Musée deRodin. Here the young poet shared the life of the aged sculptor and hismost silent hours.

Rodin felt that Rilke approached his sculptures from the sameimaginative sphere whence his own creative impulse sprang; he knewthat in the pellucid and illuminating realm of the poetic his worksfound their spiritual home as their material manifestation partook ofthe atmosphere when placed under the open sky, given wholly to the sunand wind and rain.

H. T.

AUGUSTE RODIN

"Writers work through words—Sculptors through matter"—PomponiusGauricus in his essay, "De Sculptura" (about 1504).

"The hero is he who is immovably centred."—Emerson.

Rodin was solitary before fame came to him and afterward he became,perhaps, still more solitary. For fame is ultimately but the summary ofall misunderstandings that crystallize about a new name.

Rodin's message and its significance are little understood by themany men who gathered about him. It would be a long and weary task toenlighten them; nor is this necessary, for they assembled about thename, not about the wo