Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully aspossible, including inconsistencies in spelling and hyphenation;changes (corrections of spelling and punctuation) made to theoriginal text are marked like this.The original text appears when hovering the cursor over the marked text.

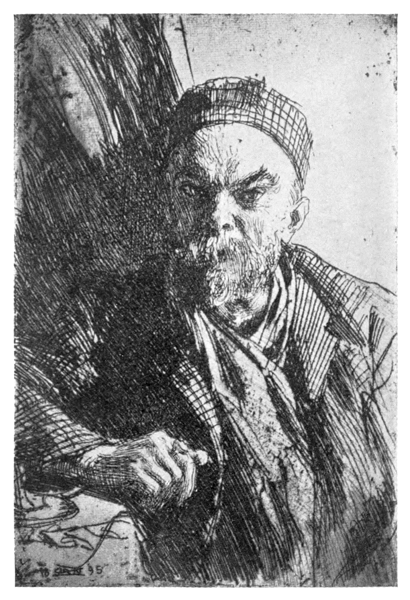

PAUL VERLAINE

By STEFAN ZWEIG

Authorized Translation by

O. F. THEIS

LUCE AND COMPANY

BOSTON

MAUNSEL AND CO., LTD.

DUBLIN and LONDON

Copyright, 1913,

By L. E. Bassett

Boston, Mass., U. S. A.

PAUL VERLAINE

PRELUDE

The works of great artists are silentbooks of eternal truths. And thus it isindelibly written in the face of Balzac,as Rodin has graven it, that the beautyof the creative gesture is wild, unwillingand painful. He has shown thatgreat creative gifts do not mean fulnessand giving out of abundance. On thecontrary the expression is that of onewho seeks help and strives to emancipatehimself. A child when afraidthrusts out his arms, and those that arefalling hold out the hand to passers-byfor aid; similarly, creative artists projecttheir sorrows and joys and all theirsudden pain which is greater than theirown strength. They hold them out likea net with which to ensnare, like a rope by which to escape. Like beggars onthe street weighed down with miseryand want, they give their words to passers-by.Each syllable gives relief becausethey thus project their own lifeinto that of strangers. Their fortuneand misfortune, their rejoicing andcomplaint, too heavy for them, aresown in the destiny of others—manand woman. The fertilizing germ isplanted at this moment which is simultaneouslypainful and happy, and theyrejoice. But the origin of this impulse,as of all others, lies in need, sweet, tormentingneed, over-ripe painful force.

No poet of recent years has possessedthis need of expressing his life to others,more imperatively, pitifully, or tragicallythan Paul Verlaine, because noother poet was so weak to the press ofdestiny. All his creative virtue is reversedstrength; it is weakness. Sincehe could not subdue, the plaint aloneremained to him; since he could notmould circumstances, they glimmer in naked, untamed, humanly-divinebeauty through his work. Thus he hasachieved a primæval lyricism—purehumanity, simple complaint, humbleness,infantile lisping, wrath and reproach;primitive sounds in sublimeform, like the sobbing wail of a beatenchild, the uneasy cry of those who arelost, the plaintive call of the solitarybird which is thrown out into the duskof evening.

Other poets have had a wider range.There have been the criers who with aclarion horn call