A Brief History

of

ELEMENT DISCOVERY,

SYNTHESIS, and ANALYSIS

Glen W. Watson

September 1963

LAWRENCE RADIATION LABORATORY

University of California

Berkeley and Livermore

Operating under contract with the

United States Atomic Energy Commission

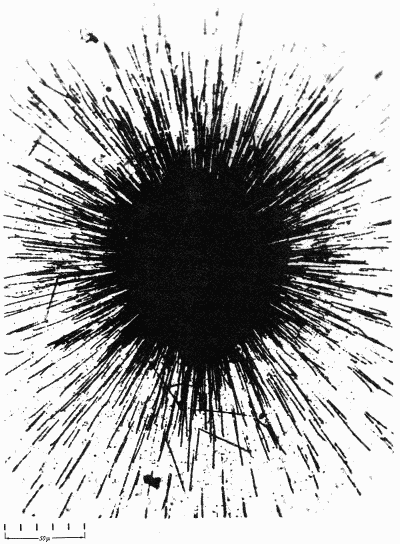

Radioactive elements: alpha particles from a speck of radiumleave tracks on a photographic emulsion. (Occhialini and Powell, 1947)

Radioactive elements: alpha particles from a speck of radiumleave tracks on a photographic emulsion. (Occhialini and Powell, 1947)A BRIEF HISTORY OF

ELEMENT DISCOVERY, SYNTHESIS,

AND ANALYSIS

It is well known that the number of elements has grown fromfour in the days of the Greeks to 103 at present, but the change inmethods needed for their discovery is not so well known. Up until1939, only 88 naturally occurring elements had been discovered.It took a dramatic modern technique (based on Ernest O. Lawrence'sNobel-prize-winning atom smasher, the cyclotron) to synthesizethe most recently discovered elements. Most of theserecent discoveries are directly attributed to scientists working underthe Atomic Energy Commission at the University of California'sRadiation Laboratory at Berkeley.

But it is apparent that our present knowledge of the elementsstretches back into history: back to England's Ernest Rutherford,who in 1919 proved that, occasionally, when an alpha particlefrom radium strikes a nitrogen atom, either a proton or a hydrogennucleus is ejected; to the Dane Niels Bohr and his 1913 ideaof electron orbits; to a once unknown Swiss patent clerk, AlbertEinstein, and his now famous theories; to Poland's Marie Curiewho, in 1898, with her French husband Pierre laboriously isolatedpolonium and radium; back to the French scientist H. A. Becquerel,who first discovered something he called a "spontaneousemission of penetrating rays from certain salts of uranium"; tothe German physicist W. K. Roentgen and his discovery of x raysin 1895; and back still further.

During this passage of scientific history, the very idea of"element" has undergone several great changes.

The early Greeks suggested earth, air, fire, and water as beingthe essential material from which all others were made. Aristotleconsidered these as being combinations of four properties: hot,cold, dry, and moist (see Fig. 1).