DR. KOMETEVSKY'S DAY

By FRITZ LEIBER

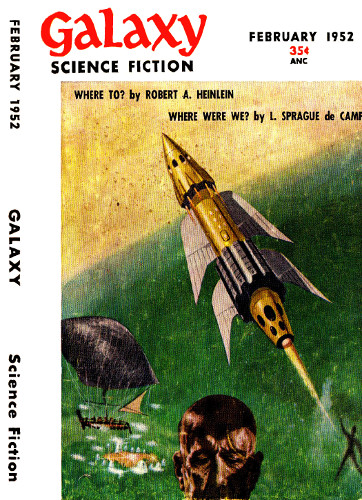

Illustrated by DAVID STONE

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction February 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Before science, there was superstition. After

science, there will be ... what? The biggest,

most staggering, most final fact of them all!

"But it's all predicted here! It even names this century for the nextreshuffling of the planets."

Celeste Wolver looked up unwillingly at the book her friend MadgeCarnap held aloft like a torch. She made out the ill-stamped title,The Dance of the Planets. There was no mistaking the time ofits origin; only paper from the Twentieth Century aged to thatparticularly nasty shade of brown. Indeed, the book seemed to Celestea brown old witch resurrected from the Last Age of Madness to confounda world growing sane, and she couldn't help shrinking back a trifletoward her husband Theodor.

He tried to come to her rescue. "Only predicted in the vaguest way. AsI understand it, Kometevsky claimed, on the basis of a lot of evidencedrawn from folklore, that the planets and their moons trade positionsevery so often."

"As if they were playing Going to Jerusalem, or musical chairs,"Celeste chimed in, but she couldn't make it sound funny.

"Jupiter was supposed to have started as the outermost planet, and isto end up in the orbit of Mercury," Theodor continued. "Well, nothingat all like that has happened."

"But it's begun," Madge said with conviction. "Phobos and Deimos havedisappeared. You can't argue away that stubborn little fact."

That was the trouble; you couldn't. Mars' two tiny moons had simplyvanished during a period when, as was generally the case, the eyesof astronomy weren't on them. Just some hundred-odd cubic miles ofrock—the merest cosmic flyspecks—yet they had carried away with themthe security of a whole world.

Looking at the lovely garden landscape around her, Celeste Wolver feltthat in a moment the shrubby hills would begin to roll like waves, thecharmingly aimless paths twist like snakes and sink in the green sea,the sparsely placed skyscrapers dissolve into the misty clouds theypierced.

People must have felt like this, she thought, when Aristarches firsthinted and Copernicus told them that the solid Earth under their feetwas falling dizzily through space. Only it's worse for us, because theycouldn't see that anything had changed. We can.

"You need something to cling to," she heard Madge say. "Dr. Kometevskywas the only person who ever had an inkling that anything like thismight happen. I was never a Kometevskyite before. Hadn't even heard ofthe man."

She said it almost apologetically. In fact, standing there so frank andanxious-eyed, Madge looked anything but a fanatic, which made it muchworse.

"Of course, there are several more convincing alternateexplanations...." Theodor began hesitantly, knowing very well thatthere weren't. If Phobos and Deimos had suddenly disintegrated,surely Mars Base would have noticed something. Of course there was theDisordered Space Hypothesis, even if it was little more than the chancephrase of a prominent physicist pounded upon by an eager journalist.