FREEWAY

BY BRYCE WALTON

The Morrisons didn't lose their freedom.

They were merely sentenced to the highways

for life, never stopping anywhere, going no

place, just driving, driving, driving....

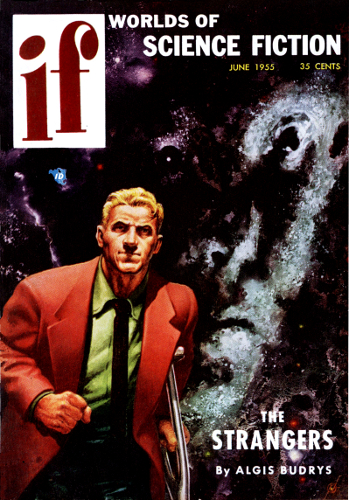

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, June 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Some people had disagreed with him. They were influential people. Hewas put on the road.

Stan wanted to scream at the big sixteen-cylinder Special to go faster.But Salt Lake City, where they would allow him to stop over for themaximum eight hours, was a long way off. And anyway, he couldn't goover a hundred. The Special had an automatic cut-off.

He stared down the super ten-lane Freeway, down the glassy river,plunging straight across the early desert morning—into nowhere. Thatwas Anna's trouble. His wife couldn't just keep travelling, knowingthere was no place to go. No one could do that. I can't do it muchlonger either, Stan thought. The two of us with no place to go but backand forth, across and over, retracing the same throughways, highways,freeways, a thousand times round and round like mobile bugs caught in agigantic concrete net.

He kept watching his wife's white face in the rear-view mirror. Nowthere was this bitter veil of resignation painted on it. He didn't knowwhen the hysteria would scream through again, what she would try next,or when.

She had always been highly emotional, vital, active, a fighter. TheSpecial kept moving, but it was still a suffocating cage. She needed tostop over somewhere, longer, much longer than the maximum eight hours.She needed treatment, a good long rest, a doctor's care—

She might need more than that. Complete freedom perhaps. She had alwaysbeen an all-or-nothing gal. But he couldn't give her that.

Shimmering up ahead he saw the shack about fifty feet off the Freeway,saw the fluttering of colorful hand-woven rugs and blankets coveredwith ancient Indian symbols.

It wasn't an authorized stop, but he stopped. The car swayed slightlyas he pressed the hydraulic.

From the bluish haze of the desert's tranquil breath a jackrabbithobbled onto the Freeway's fringe. It froze. Then with a squeal itscrambled back into the dust to escape the thing hurtling toward it outof the rising sun.

Stan jumped out. The dust burned. There was a flat heavy violence tothe blast of morning sun on his face. He looked in through the rearwindow of the car.

"You'll be okay, honey." Her face was feverish. Sweat stood out on herforehead. She didn't look at him.

"It's too late," she said. "We're dead, Stan. Moving all the time. Butnot alive."

He turned. The pressure, the suppression, the helpless anger was in himmeeting the heavy hand of the sun. An old Indian, wearing dirty levisand a denim shirt and a beaded belt, was standing near him. His facewas angled, so dark it had a bluish tinge. "Blanket? Rugs? Hand-made.Real Indian stuff."

"My wife's sick," Stan said. "She needs a doctor. I want to use yourphone to call a doctor. I can't leave the Freeway—"

This was the fourth unauthorized stop he had made since Anna had triedto jump out of the car back there—when it was going a hundred miles anhour.

The Indian saw the Special's license. He shrugged, then shook his head.

"For God's sake don't shake your head," Stan yelled. "Just let me useyour phone—"

The Indi