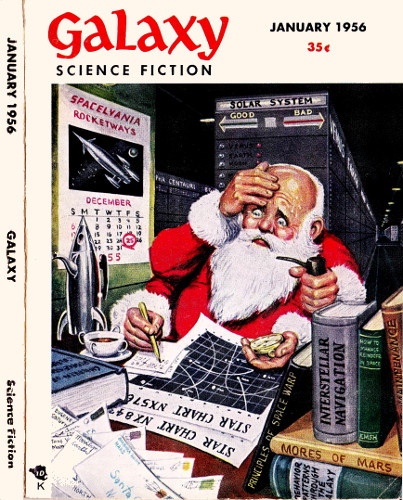

The Gravity Business

By JAMES E. GUNN

Illustrated by ASHMAN

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy January 1956.Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyrighton this publication was renewed.]

This little alien beggar could dictate his own terms, but how couldhe—and how could anyone find out what those terms might be?

The flivver descended vertically toward the green planet circling theold, orange sun.

It was a spaceship, but not the kind men had once dreamed about. Theflivver was shaped like a crude bullet, blunt at one end of a fatcylinder and tapering abruptly to a point at the other. It had beenslapped together out of sheet metal and insulation board, and it sold,fully equipped, for $15,730. It didn't behave like a spaceship, either.

As it hurtled down, its speed increased with dramatic swiftness. Then,at the last instant before impact, it stopped. Just like that.

A moment later, it thumped a last few inches into the ankle-deep grassand knee-high white flowers of the meadow. It was a shock of a jar thatmade the sheet-metal walls boom like thunder machines. The flivverrocked unsteadily on its flat stern before it decided to stay upright.

Then all was quiet—outside.

Inside the big, central cabin, Grampa waved his pircuit irately in theair. "Now look what you made me do! Just when I had the blamed thingpractically whipped, too!"

Grampa was a white-haired 90-year-old who could still go a fast roundor two with a man (or woman) half his age, but he had a habit oflapsing into tantrum when he got annoyed.

"Now, Grampa," Fred soothed, but his face was concerned. Fred, oncecalled Young Fred, was Grampa's only son. He was sixty and his hair hadbegun to gray at the temples. "That landing was pretty rough, Junior."

Junior was Fred's only son. Because he was thirty-five and capableof exercising adult judgment and because he had the youngest adultreflexes, he sat in the pilot's chair, the control stick between hisknees, his thumb still over the Off-On button on top. "I know it,Fred," he said, frowning. "This world fooled me. It has a diameterless than that of Mercury and yet a gravitational pull as great asEarth."

Grampa started to say something, but an 8-year-old boy looked up fromthe navigator's table beside the big computer and said, "Well, gosh,Junior, that's why we picked this planet. We fed all the orbital datainto Abacus, and Abacus said that orbital perturbations indicated thatthe second planet was unusually heavy for its size. Then Fred said,'That looks like heavy metals', and you said, 'Maybe uranium—'"

"That's enough, Four," Junior interrupted. "Never mind what I said."

Those were the Peppergrass men, four generations of them, lookingremarkably alike, although some vital element seemed to have dwindleduntil Four looked pale and thin-faced and wizened.

"And, Four," Reba said automatically, "don't call your father 'Junior.'It sounds disrespectful."

Reba was Four's mother and Junior's wife. On her own, she was ared-haired beauty with the loveliest figure this side of Antares. ThatJunior had won her was, to Grampa, the most hopeful thing he had evernoticed about the boy.

"But everybody calls Junior 'Junior,'" Four complained. "Besides, Fredis Junior's father